Curiosity meets Resonance, part 1

"Writing about music is like dancing about architecture" - unknown

It is easier to understand sound when you can see it, and that makes it easier to discuss as well. That is the basic principle that sent me down the road of studying resonances in instruments using Fast Fourier Transforms. A Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) takes a recorded sound and displays the frequencies that make it up. If you want to know more about a sound or tone, FFT can show you a lot. My aim here is to share my experience getting started with resonances and FFT.

I was first interested to know what different tones look like graphically. In FFT graphs, the frequency (measured in Hz) is plotted along the x-axis, and the volume (measured in deciBells (dB)) is plotted on the y-axis. The taller a peak is, the louder is. Peaks to the left are lower in pitch and peaks to the right are higher in pitch. There are many programs which will turn recordings into FFT’s. For this write-up, I have been using Audacity and the “plot spectrum” tool. For reasons I’ll explain at a different time, I am only interested in frequencies less than 5,000 Hz.

To get started, I decided to tap various objects and record and graph them. I started with some wooden things, then some metal things, then plucked some strings. Then I looked at instruments: first a banjo and then a ukulele, then I finally got into it with mandolins. My actual experience over the last year has been way more circuitous than this but I am presenting here a flow for how it began making sense to me— the idealized version of my experience. And I want to maintain the sense of exploration so I will avoid, for now, using some official terms for phenomena that are about to be shown— I will address those in future posts as I expand on my process. I want to share my story and invite you into the mystery of tone and how I have experienced it through building and exploring!

Wooden Things

Spruce wedge hit with a felt mallet, (I wrote this over a few days so "felt mallet" and "felt hammer" are the same thing)

This is a wedge of spruce that is roughly 18“ long, 7" wide and 3/4” thick on one side and about 1/4” thick on the other. I'm holding it on the long thick edge about 1/4 the way from an end and tapping it in the middle with a felt covered wood hammer. Each peak on this graph is a resonant frequency in the piece of wood. You can see the highest peak is at 511 Hz, which is near the C above middle C— that’s the main note that can be heard. In person it is hard to tell there are more than one or two frequencies present, but the FFT graph shows that there are several.

Point: most sounds are made of more than one frequency

Spruce Wedge hit with a steel hammer

This is the same spruce wedge, this time tapped with a steel hammer, held and hit in the same place as before. You can see the same frequencies show up, but in different heights and ratios compared to each other. Imagine the sound difference between a soft and a hard hammer hitting the same thing, this is the graph version of that. The main note is the same (511 Hz) but the tone is different (different arrangement of higher frequencies).

Point: the same material, with the same resonant frequencies can sound different if hit by different things (or in different ways) and this is because of differences in the upper resonant frequencies

Mahogany billet hit with felt mallet

Here is a piece of mahogany, roughly 18" long, 12" wide and 3/4" thick. This piece of wood has many more resonant frequencies than the spruce, even though it is hit by the same hammer and held in a similar way. This is due to the different properties of mahogany vs spruce including its stiffness, density, dimensions and grain.

Point: different materials will have different resonant frequency trends depending on their physical characteristics

Mahogany billet hit with steel hammer

The same piece of mahogany shows many more peaks when hit with the steel hammer, particularly above 2500 Hz. What does 2500 Hz sound like? Listen here, it’s quite annoying, like the first tone of a fax machine or dial up modem, or an appliance alert beep.

Point: not only can resonant frequencies change in relative volume, some frequencies can appear and disappear depending on how and with what you excite them. The higher frequencies usually require more force and/or heavier strikers

Metal Things

Steel Bowl hit with felt hammer

Looking now at thin gauge metal (it is ~ .012" thick) we get skinnier peaks compared to wood. The spacing on these peaks is wider and there is a regularity to them. The skinniness and smoothness of the metal resonance peaks has to do with its density and stiffness and homogenous composition compared to wood.

Point: compared to wood, metal makes skinnier and smoother peaks.

Square Steel Tube hit with felt hammer

This 1/2" steel tube (.06" thick walls, 5x thicker than the bowl) also has skinny peaks, but the bases of the peaks are also skinny and distinct from each other. I think it's because a steel tube is considerably thicker and stiffer and narrower than the bowl.

Point: the denser, narrower and stiffer the material, the skinnier the peak appears to be

Strings

Electric guitar, open low e string (82 Hz), unamplified:

An electric guitar string does not excite the dense body into vibrating very much, so we see the characteristic tall skinny peak of a metal string. Notice the clear peak of the fundamental at 82 Hz. Note also that the first harmonic (second peak at 165 Hz) is taller (louder) than the first. This louder first harmonic is quite common in vibrating strings. Side-note: next time you are near the low e string on a guitar, see if you notice the first harmonic is louder than the fundamental, it might be!

Point: strings are metal, so string peaks are skinny

Banjo

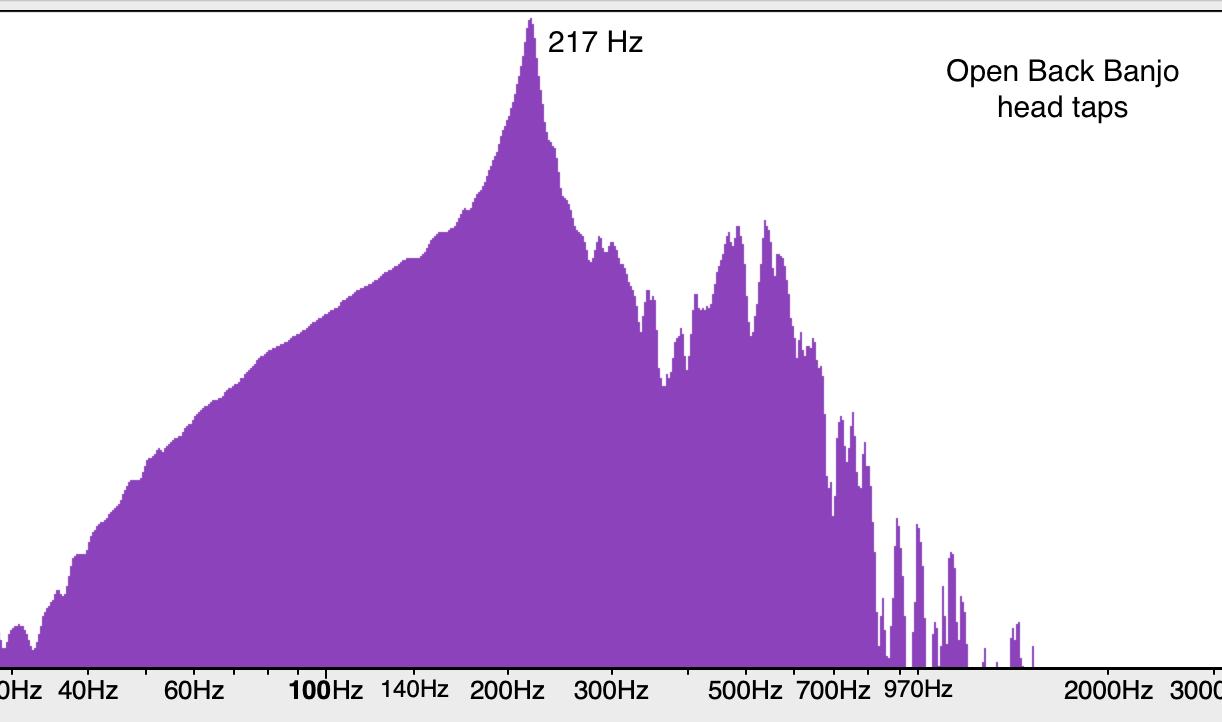

Banjo head: light and flexible surface

The main resonant peak of a banjo head (polymer head strung up but the strings are muted), has an onion shape with a very wide swooping base and a tapering peak. The other peaks in the graph around 300 Hz+ are not something we will concern ourselves with today.

Point: less dense and less stiff and lighter surfaces have resonant peaks with wide bases. Flexibility seems to allow a surface to resonate at a wider range of frequencies and support other resonances on top of that. Drag your finger over a piece of paper, or a banjo head or a thin piece of spruce and it sounds like white noise (all frequencies at once)— very different from a metal surface or a thicker/heavier piece of wood.

Strings on a Banjo

Here we have a plain open high g string (397 Hz) played on the open-back banjo. You can see the wide base and skinny top of the fundamental frequency, as well as the harmonics with relatively wide bases compared to the following examples.

Point: peak shape seems to be a process of addition from the source materials, wide base and skinny top fits the profile of a metal string on a banjo head. Also, strings are good conveyors of harmonic resonances.

Ukulele

Wooden Box: Tenor Ukulele

This is the wood portion of a tenor ukulele, only tapping the top of the instrument with the felt hammer and muting the strings like I did with the banjo. You can see the main resonance at 187 Hz. You can see there are several modes of vibration happening at the same time in the wooden box. Also note the wide bases and irregular tapering peaks.

Point: a wooden box has multiple resonances like other wooden things

Tenor Ukulele C string (262 Hz), open

A tenor ukulele open C string (262 Hz) creates a fundamental with a wide base, as well as a wider base on the first harmonic. Interesting note: There is a shoulder (187 Hz) on the left side of the fundamental peak. This is the 187 Hz resonance in the graph above, the one we saw when tapping the body with the strings muted. We will see this again very soon.

Mandolin

Mandolin Body Resonances

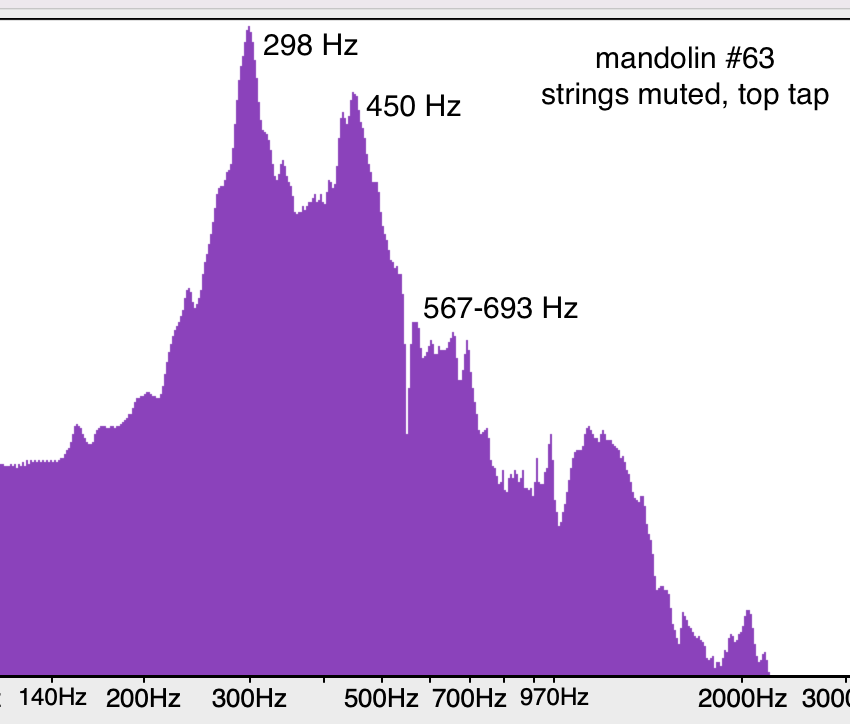

Wooden box: mandolin top taps

Like with the tenor ukulele, here is the tap of a mandolin when only the top is tapped with the felt hammer and the strings are muted. The two main peaks to keep track of here are 298 Hz and 450 hz. See how wide and tapered they are compared to string peaks.

Point: whether ukulele shaped or mandolin shaped, a wooden box acts like wood

Mandolin tapped on top AND back

Let's tap the back as well as the top on this mandolin. Note the first two peaks are the same (298 and 450 Hz), but now there is a third main peak at 567Hz. This frequency peak wasn’t very prominent in the first graph, and really only showed up when we tapped the back, so it must come from the back. This method of elimination can be used to figure out where most of the important resonances come from. The method will also show which frequencies show up in more than one place. For instance, on this instrument, 298 Hz will show up just about anywhere you excite the instrument--ESPECIALLY if you blow over the soundholes... more on that in a later post!

Point: when tapped, each resonant peak corresponds with some part of the box itself

Mandolin Strings

Mandolin open strings

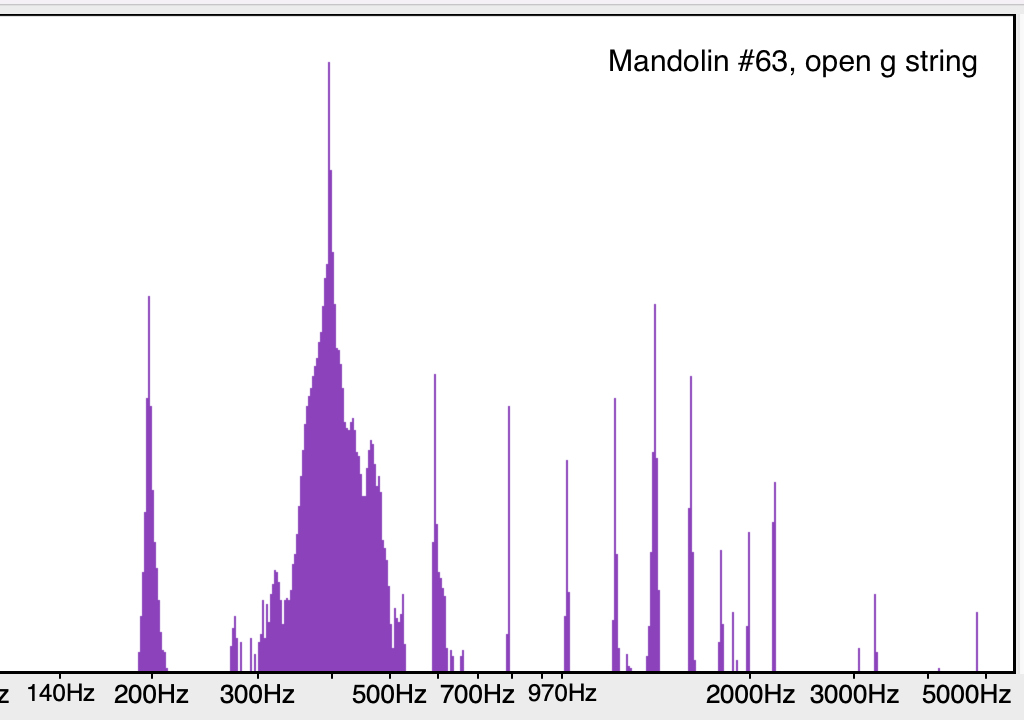

Open G (196 Hz)

The open G (196 Hz) on the mandolin has a much more prominent first harmonic (392 Hz) than fundamental. This is typical of the lower range notes of most mandolins. The first harmonic peak (392 Hz) has a wide base that covers the first two tapping resonances (298 Hz and 450 Hz). When hearing the open G, your brain says you are hearing the 196 Hz frequency, but if you listen for it you'll notice the first harmonic is actually louder! This is true of many mandolins and is a byproduct of our physiology. See also that there are 6 more prominent harmonics after the first, nearly all detectable with your ear, but they aren’t obvious to most people, you have to listen for them.

Point: resonances in the wood interact with resonances of the strings, even the harmonics of the string

Open D (293.6 Hz)

The open D frequency (293.6 Hz) is very close to the first highest tapping peak (298 Hz) on this instrument, so it gets a wide base and remains broader to the top when compared with the open g strings. Its harmonics are evenly spaced and pointy (but not all the same height, nor evenly diminishing). And here there are only 3 or 4.

Open A (440 hz)

The wide base of the open A (440 Hz) leans heavy to the left and you can see a small peak at 294 Hz, the first tapping resonance. The right side of the fundamental peak drops off at a steep angle. The second tapping frequency of 450 Hz shows up as a slight shoulder on the right side. The three harmonics are pointy and relatively weak.

Point: Having a body resonance nearby causes a string peak to have a wider base.

Open E (659.25 Hz)

The open E fundamental peak (659.25 Hz) is a stand-alone, peaky peak. It has three harmonics associated, one barely registering. But noteworthy here is the clump of peaks to the left of the fundamental which are the tapping frequencies of the body of the mandolin, and separate from the base of the fundamental peak. So, playing the e strings also excites these LOWER tapping frequencies. Just as it did on the open A, and just as it does on many more notes.

Point: the act of picking a string can excite the tapping frequencies of the body, even if they have no apparent relationship to the frequency of the string.

Take Aways

o Most sounds are made of more than one frequency

o The same material, with the same resonant frequencies can sound different if hit by different things

o Material properties like density, hardness, dimension and stiffness determine how a thing will vibrate when excited

o Not only can resonant frequencies change in relative volume, some frequencies can appear and disappear depending on how and with what you excite them

o Compared to wood, metal makes skinnier and smoother peaks because it is denser and stiffer. We are starting to see how tone can be visualized graphically.

o Less dense, less stiff ,and lighter surfaces have resonant peaks with wide bases. Flexibility seems to allow a surface to resonate at a wider range of frequencies and support other resonances on top of that.

o When tapped, each resonant peak corresponds with some part of the instrument, and some frequencies can be found in more than one part.

o Resonances in the wood interact with resonances of the strings

For kicks: Here's the last graph of the open E of one of my favorite mandolins (#63) next to the graph of the open E of one of my least favorite mandolins (mandolin X). Note how similar the graphs are in structure, but also how different the two low tapping peak frequencies are.

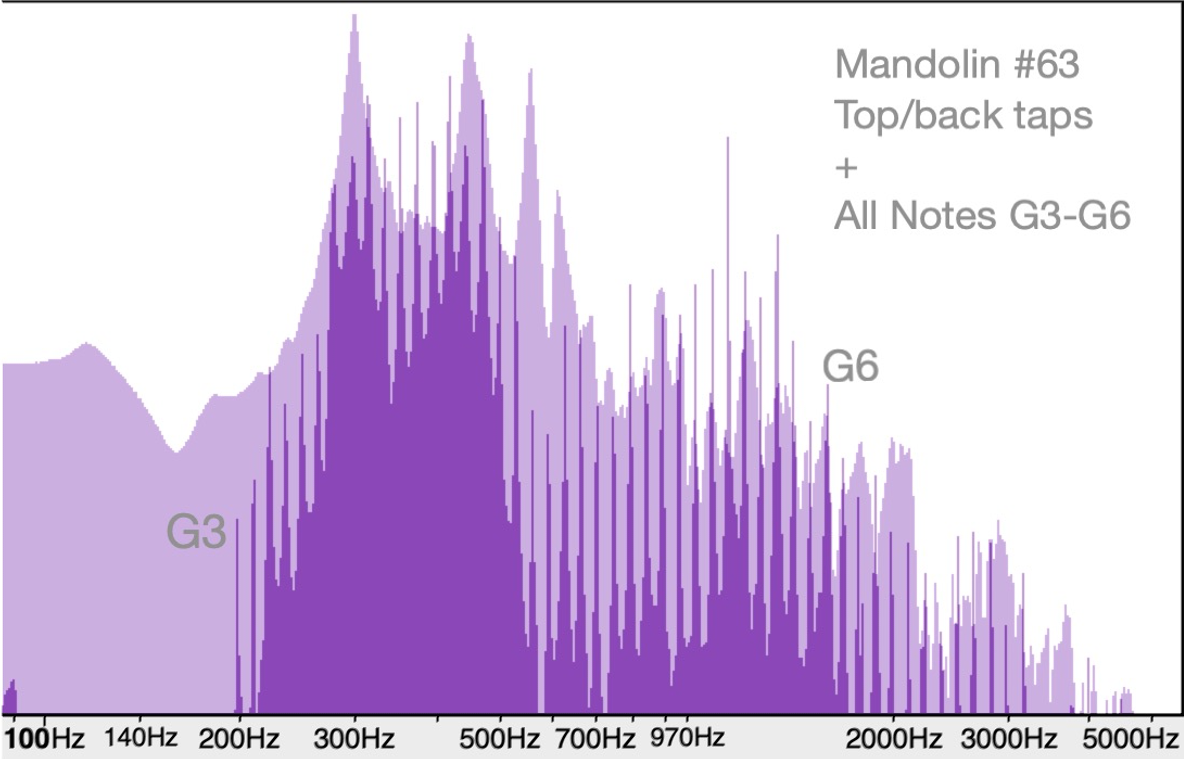

And a last teaser if you've followed along so far... Here's the top/back tapping resonances of mandolin #63 overlayed by all the notes the instrument can produce from the open low G3 (196 Hz) to the G6 (1567.98 Hz) on the 15th fret on the e strings. I am looking forward to sharing more about this in upcoming blogs…